Iran's exiled crown prince calls on hackers to attack regime's "information infrastructure"

Pahlavi Reza, son of the deposed shah, urges allies to focus on taking down the Ayatollah's digital control systems and bringing Iran back online.

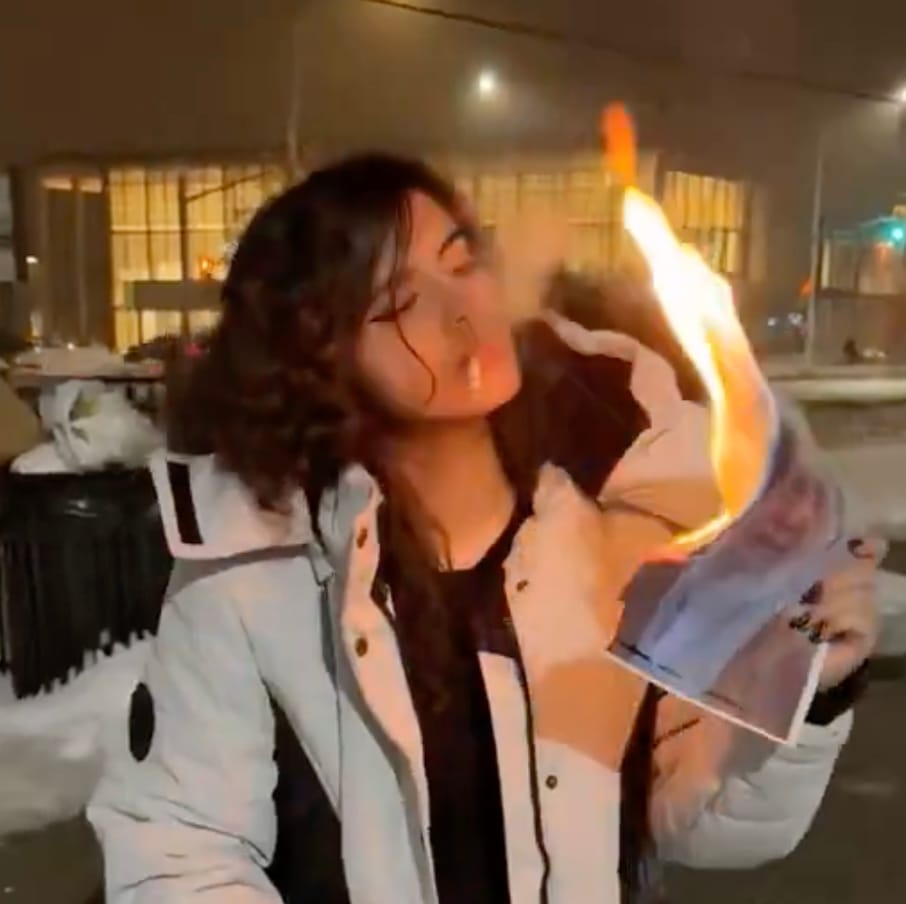

The Iranian crown prince in exile, Pahlavi Reza, has called on hackers to attack the Ayatollah's theocratic Islamic regime to end its internet blackout and restore communications with the world.

Ever since nationwide protests erupted in Iran amid worsening economic hardship and growing anger with the repressive government, Pahlavi has been supporting the demonstrators. He fled Iran with his father in January 1979 when Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini's Islamic Revolution overthrew the monarchy.

In response, the regime has killed hundreds of Iranians and cut off the internet delivered via cellphone towers and fibre-optic cables for more than 100 hours.

Although Elon Musk’s Starlink is broadcasting satellite internet to the nation, the regime has reportedly found a way of jamming signals so that Iranians cannot connect.

In an X post addressed to his "compatriots", Reza wrote: "The regime, through severe repression, killing, and cutting off communications, is trying to instill fear and terror in you, and to make you despair of continuing the movement and struggle.

"But know that because of your steadfastness and fight, thousands of military and security forces have not gone to work so as not to participate in the repression.

"And a special message to specialists in the field of internet and communications: target the regime's information infrastructure so that the connection of our compatriots with the world can be reestablished."

هممیهنانم، درود به همگی شما که بهمانند کاوه در مقابل ضحاک ایستادهاید و میجنگید.

— Reza Pahlavi (@PahlaviReza) January 13, 2026

رژیم با سرکوب شدید و کشتار و قطع ارتباطات تلاش دارد در شما ایجاد ترس و رعب کند، و شما را مایوس از ادامه حرکت و مبارزه. اما بدانید به دلیل ایستادگی و مبارزه شما، هزاران تن از نیروهای نظامی و… pic.twitter.com/4koHr31a3O

The Great Firewall of Iran

The Iranian state's internet control system is built into the structure of its network. Nearly all domestic connectivity is routed through state-controlled providers linked to the Telecommunications Infrastructure Company (TIC), giving authorities choke-points over international gateways.

On top of this sits the National Information Network (NIN), a parallel domestic intranet that hosts government services, banking, messaging, and major platforms inside Iran. In moments of unrest, traffic to the global internet can be severed while the NIN remains active, allowing the state to preserve essential services while isolating citizens from foreign media, social platforms, and external coordination.

At the packet level, Iran uses deep packet inspection (DPI) and traffic classification systems to filter, throttle, or block content in real time. DPI allows operators to inspect headers and payloads to identify protocols, keywords, domains, and encrypted tunnel signatures associated with VPNs, Tor, or proxy tools.

Requests to blocked destinations are intercepted and redirected to state block pages or silently dropped. This is not simple DNS filtering: it operates across multiple OSI layers, enabling selective interference with HTTPS traffic, application-specific throttling (e.g., video or messaging), and rapid blacklisting of newly discovered circumvention endpoints.

READ MORE: Iran "attacks US critical infrastructure with new cyberweapon"

During periods of political tension, Iran shifts from selective filtering to active traffic management and shutdown modes.

Rather than a binary “off switch,” authorities often degrade throughput so severely that video uploads, livestreaming, or large file transfers become functionally impossible while basic domestic services remain accessible.

This preserves the appearance of connectivity while neutralising the tools most useful for mass communication, documentation, and organisation.

Censorship is reinforced by legal and surveillance infrastructure. Circumvention tools are criminalised, VPN providers are periodically blocked or forced to register, and encrypted traffic is profiled for anomalous patterns.

User activity can be correlated across telecom providers and state platforms, with metadata retention enabling retroactive investigation.

In practice, this creates a layered system: architectural control at the backbone, protocol-level inspection in transit, platform blocking at the application layer, and legal deterrence at the user level.

Iran’s model of internet control is not merely about restricting content. It is designed to squeeze the network itself into a controllable, nationally bounded system that can be tightened or relaxed in response to political conditions.

Will hackers be able to pull down the veil over Iran's internet? Stay tuned for updates.